Co-creating the change we want to see: The non-negotiable for food systems transformation

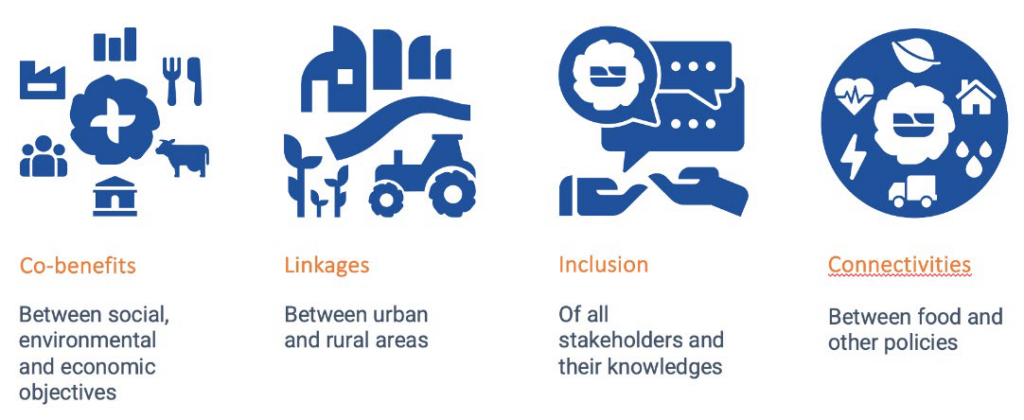

Food systems, by their very nature, cross boundaries. They cannot be siloed within a single municipality or field of expertise and societal sector, conditions under which their transformation would be difficult and rigid. That is why broadening, the expansion of both the sectors of knowledge involved (science, policy, practice, and society) and the geographies engaged, is necessary and recommended.

The FoodCLIC Broadening process is now active in eight Broadening city-regions (BCRs); three in Africa (Ebolowa, Cameroon; eThekwini, South Africa; Fort Portal, Uganda) and five across Europe (Freiburg, Germany; Thessaloniki, Greece; Tbilisi, Georgia; Tirana, Albania; Wrocław, Poland). It seeks to support city-regions in their transformation journeys using tools and approaches tested in the project’s pilot Living Labs, while also ensuring the continuation of initiatives and sharing of learnings beyond the project’s lifetime.

Co-creation, adaptation, and baseline assessments

At the heart of FoodCLIC’s Broadening process lies co-creation. The process was designed from the start to be flexible, as Broadening city-regions joined with their unique challenges, motivations, and goals, requiring a context-sensitive approach that recognizes transformation cannot be a one-size-fits-all endeavour. Yet, it is also grounded in practice through tools, templates, and peer learning that support FoodCLIC’s phased approach and have already found application in FoodCLIC’s pilot cities.

In Africa, ICLEI supported the creation of steering committees in each of the three participating cities. These groups regularly met together online to develop a preliminary workplan for the upcoming local workshops. Establishing these committees offered several benefits, fostering a sense of ownership, accountability, and buy-in, enabling genuine co-creation and continuity throughout the process, and ensuring that the voices of the BCRs were central in the workshop design. In Europe, a different approach was taken preferring one-to-one meetings and regular email communication, but also headed towards the same goal of clarifying objectives, enabling exchanges and keeping participants informed and involved. In 2024, all eight BCRs took part in peer-to-peer exchanges that laid the groundwork for local activities.

Starting in early 2025, each city-region hosted its first workshop to take stock of their city-region food systems and see which actors are engaged, using multiple participatory methodologies. These included SWOT analyses in Fort Portal and Wrocław, site visits in eThekwini’s Fresh Produce Market, and above all stakeholder mappings. The aim was to bring together and embed the perspectives of the diversity of food systems actors into baseline assessments to inform policy-making.

Even in contexts where food systems were already shaped and supported both by national policies, local projects and existing Food Policy networks, including Fort Portal, Freiburg, and Thessaloniki, the workshop brought to light the need to further include those affected by social and food systems inequities in decision-making processes. These insights underscore the importance of co-creative and inclusive approaches in developing policies that reflect the needs of all community members, while also looking at who needs to be at the table that currently is not.

The need for grounding policy in lived experiences

Notably, a recurring theme was the importance of grounding food strategies in lived realities. All workshops highlighted the urgency of designing food policies that entail cross-sectoral interventions, whilst also reflecting people’s voices, not only institutional agendas.

The workshops produced valuable insights that can, and hopefully will, shape the next project developments in each city. The eThekwini workshop, for instance, emphasized the need for its developing food strategy to connect with daily experience: while agriculture plays an important role, participants pointed out the importance of focusing also on health, market access, and the erosion of indigenous food cultures.

The spatial dimension of food systems also emerged as a key issue. In Tbilisi, discussions focused on transforming the Railway Station’s informal food market into an inclusive food center, while Freiburg has been laying the groundwork for its House of Food, a physical food hub to fuel food entrepreneurship. Other participants, such as those from Fort Portal, Ebolowa and Tirana, have also highlighted the importance of strengthening local food markets, as they are critical for local food security, nutrition, and resilience, providing spaces for diverse, healthy, and often affordable food options, while also offering economic opportunities to small-scale farmers and vendors, who may otherwise be excluded from corporate supply chains. In Wrocław, the ongoing war in Ukraine has heightened food security concerns, particularly for Ukrainian refugees, alongside other groups such as flood victims, socially excluded youth, elderly people, and those experiencing houselessness or poverty. In the Broadening activities of the city, especially the importance of gaining access to reliable data, was emphasized to effectively map and engage these communities.

Such examples highlight a cornerstone of the CLIC framework: food systems transformation requires inclusion. Without inclusion, changes risk reinforcing inequalities. And too often, people least represented in governance processes are the most vulnerable to food crises and insecurity.

What’s next?

The first round of workshops ended with shared resolutions to continue working on strategic planning and looking at how governance arrangements can become more inclusive. Several city-regions are moving in this direction, many with plans to create a Food Policy network, or strengthen participation and co-creation in the previously existing food-related institutions. In the European context an exciting initiative is soon being launched in this regard: the European Platform for Food Policy Networks, an online exchange space for networks and groups working on food and food policy across Europe.

The baseline assessments and discussions also revealed additional areas of action, including the need to integrate food across municipal mandates, addressing food security and engaging the community. The central challenge isn’t just about including more voices. It’s about understanding who needs to be at the table, showing why their input matters, and that real change, benefitting those that have been rendered most vulnerable due to socially produced inequalities, is possible. While it is a process that takes time, trust and genuine efforts to learn, listen and act, it is precisely this investment that fuels lasting change and genuine transformation in food systems.

Looking ahead, the Broadening process aims to create adaptable, yet locally grounded frameworks to shape pathways of change in food systems across city-regions. The next phase, running through August 2026, will take city-region projects from baseline assessments to long-term strategic planning and visioning – building more resilient, sustainable and accessible food systems, for everyone.

This blog was written by Flora Allesina and Matteo Bizzotto, ICLEI World Secretariat, based on the FoodCLIC’s “First Progress report on Broadening in eight Broadening city-regions.”